Welcome to Tarquinius W. Peterson’s Fantastical Guide to the World of Art.

This week we are uncovering …

The Scream by Edvard Munch, 1893

Everyone knows this artwork, but that’s not surprising, as several, several copies exist today. By copies, I mean versions. Since version 1.0 Mr Munch endeavoured, over several decades—even centuries—to exploit the world’s art market in producing upgrades and variations. Versions 1.1 to 1.3 exist, along with an offshoot version 2.0 and then moving on to version 3.0, which became, and still is, the most successful icon of modern art ever, period.

How did this Norwegian expressionist son of priest takeover the world? Tarquinius W. will explain.

With a catalogue of versions flooding the market, bent on world domination, we need to examine each on individual terms. But, where to be begin?

Firstly, I apologise to the other artists, sculptors and creators of various art forms whom I have or will put under the Peterson spotlight and magnifying glass, because as a general rule, I scrutinise individual pieces. In greedy Mr Muncher’s abuse of galleries and critics like myself, Tarquinius W. Peterson, he inadvertently, or deliberately as is more likely, created numerous variations—the idea revisited later by American pop artist Andrew Warhola, and manipulated, although not as successful as Ed.

So, we start with versions 1.0 through to 1.3 of The Scream. Or is it The Scream?

Over the years, confusion with reference to the artwork’s title prevails. Those uneducated, refer to this piece as The Cry (an alternate translation from the Norwegian word: shrik, which means scream, or cry), but a handful of lazy critics use the title The Shriek (which comes from not translating the Norwegian word: shrik). It doesn’t stop there! Edvard Munch produced and exhibited most of his work in Germany, and his version 2.0 below carries the words Das Geschrei which, in Deutsche, translates to the above words, and: yell, clamour, wail, shout, or howl! For clarity, Tarquin chooses The Scream.

An observation we note straight away is that Eddie the Artist is a staunch environmentalist. This began when an online purchase of a multipack of canvases arrived from Amazon. Munch, annoyed by the volume of unnecessary packaging material, became infatuated with the texture and colour of the brown corrugated cardboard, so much so, he stored the canvases, kept the packaging and used it as the base substrate for version 1 editions of the artwork, as follows …

Version 1.0

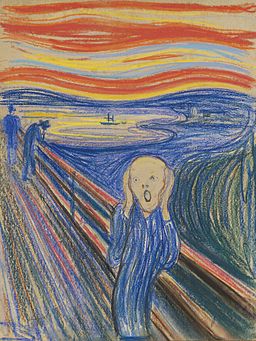

The Scream [1893]: pastel on cardboard (see).

Very sketchy pastel, although Munch didn’t deviate from this composition to those of his oils, so he must have gone with his first idea—not much development IMHO.

Note: Are the characters in the background impaled in, or on, the railings, producing cause for the scream?

Version 1.1

The Scream [1893]: oil, tempera (the technique of mixing paint with egg yolk to form a smelly watery miscible emulsion, yeah, weird) and pastel (again) on cardboard.

Everyone’s seen this popular version which hangs in Oslo’s National Gallery and copied in most reference books.

Note: The head severed from one of the background characters could be a screaming cause.

Version 1.2

The Scream [1895]: pastel on cardboard (again, see).

Created two years after 1.1, the only known version outside Norway, and sold at a bigly price in 2012. Near to US$120 million to be inexact and to a private collection, but not that private, a well known rich-guy called Leon Black—’We know where you live, Leon!’

Note: Only a single boat sails on the sea in this version and this could be the catalyst for a scream due to the horror of a sunken vessel.

Version 1.3

The Scream [1910]: tempera on (more) cardboard.

Yet another one, and probable grounds for exploitation of the market. At this time, it is certain that he couldn’t dislodge the disturbed image from of his head. Also, with only tempera, it’s an eggy version. It is curious that someone liked the oeuffy aroma of this painting: nicked from Munch Museum in 2004 and recovered in 2006 with bite marks.

Note: It is clear in this version that a scream emanated because the screamer lost both his or her eyes.

Version 1.4—A T.W.P. Exclusive

Rumoured to exist, is a version 1.4, but the whereabouts unknown. This is because during WW2 the then owner, a clever German Jewish gentleman, hide it from the scumbag Nazi’s and Hitler—who once said of Munch and his arty pals: “… (they) art-stutterers can return to the caves of their ancestors and there can apply their primitive international scratching.”—fascist.

It is within the bounds of practicability therefore, that hidden away in a forgotten dark, damp cave at the edge of a Norwegian fjord, a missing 1.4 lives disguised in discarded cardboard packaging washed-up on the beach.

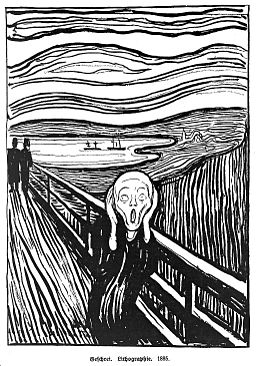

The Scream [1895]: lithograph.

So, following on the great success of his return to pastel in version 1.2, Edvard turned thoughts to “limited edition” print runs on litho. 45 rare prints, made before the printer rejigged the stone plate, are catching huge sums on eBay. The most sort after are the ultra-rare hand-coloured editions by Eddie, I recommend checking-out the local Oslo car-boots when visiting.

Note: The screaming person in this work exhibits a sideways glance to an action the other figures may have done.

Version 3.0

Edvard Munchenbaby decided he’d had enough of producing rarities for rich art collectors, so in answer to increasing globalisation he worked on a cheaper mass-market edition: his “Face Screaming in Fear” emoji.

Designed to resemble a digital version of The Scream and available world-wide as Unicode emoji rendering U+1F631:

?

Disguised as a piddly commission of US$0.005 for each use, this product placement has grown to multi-million dollar royalties for Munch’s estate, and still grows. The fee generates every time someone sends a Screaming Face text, or email, or renders this blog page to read it—which comes to at least a US$0.015 commission alone.

Influence

Money aside, a few questions that come to mind—other than, was Eddivard Munch a globalisation fundamentalist, or just a cool brand icon builder?

What influenced The Scream?

Who was the Screamer?

Why, in his return to the pastel colours in version 1.2, does the unobserved figure on the left appear to be throwing-up over the handrail? Is it a shock reaction inline with the screamer’s scream, or just more realism than shown in the kiddy-style faces and silly hats in version 1.0?

Tarquinius, author of the Fantastical Guide, can let you in on a recent discovery with regarding the composition, and to the fellow in the foreground who influenced this great representation of expressionism. After a long, long, and extensive research of waterways, lakes and oceans in and around Scandinavia, Tarquinius can reveal that a relevant event occurred at the Munch’s mansion in the city of Christiania (now named Oslo), not long after moving to their new house. The Munch’s didn’t have much, the house was a step-up from the farmhouse where they lived before—the birth place of Munch—and his father’s pious Lutheran ways lead to a simple life.

So, The Incident!

When he was only four-years-old Edvard’s mother, suffering the onset of TB, crashed their horse-drawn buggy into a tree trying to negotiate through their garden gate. Edvard, thrown from the horsey jalopy into the tree, suffered head trauma. His father went ballistic with rage, although abstained from blasphemous comments, berating mother and son. Edvard’s Pops was not the influence for screamer. Edvard, the self-diagnosed madman, blamed his father for his insane inheritance.

The shock of the buggy incident effected his mother and hastened her consumption. Although, combined effects of pain, shock and horsey embarrassment on his mother’s face did not coerce Munch’s artistic talent in determining The Scream‘s facial expression either. Neither, while he enjoyed self-portraiture, did Eddie’s own saddened reflection following the death of his mother help with the haunting shrieking cryer.

T.W. Peterson deduces that no single human emotion, or mixture of emotions foretold in individual family faces aided the painting’s grimace. Instead, Eddie Munchie—not to be confused with the original 1957 Munchie sweets, produced by English company Macintosh (not the Swiss Nestlé copies)—was himself possessed my the local vicinity where the accident took place.

In a timeline, far into the future, one copy of the The Scream, pursued by timelord, Sylvester McCoy, hangs on a dust planet called Duchamp 331. And yes, the famous Frenchman manufactured the Art Gallery and Showroom planet, but we’ll cover Marcel Duchamp, his impromptu meeting with our Eddy Munchy, and his planet building abilities in another post.

When Mrs Munch crashed into the tree, Edvard inhaled dust from under the tree’s bark, which transformed in the young child’s brain to the Warp Core: an alien fighting force; and only defeater of the unstoppable, biologically-engineered killers: the Krill (ask a Whovian for further information).

The route of Munch’s mental energy and tormented psychological thoughts, according to the seventh Doctor, lay within this Warp Core and exerted a powerful influence on the artist. Driven by decade-long battles with his brain, Munch sort to exorcise the alien into The Scream pastel dust, and bound it to the cardboard’s corrugation behind the howling screamer.

This alternate Munchian-influenced timeframe and sequence of spacial events must not be confused with the The Silence; another alien race, whom resemble incarnations of Edvard’s screaming creature. These aliens only look similar and, as their name suggests, they don’t yell or howl. Their bizarre characteristic is humans are not conscious of their existence, only a “subconscious awareness”, the moment a Silent turns their back humans completely forget them. In the future, the eleventh doctor, Matt Smith, is foreseen dying by a Silent, further into the future. To expand more on this, I need a study course on quantum physics, plus Dr Who’s not human, and I can’t get my head around such a scenario; I’m an art critic not a rocket-scientist.

So, the real concept for The Scream was not weird looking aliens or the artist’s mind-blowing mental disorder, but a beech tree. This Warp-Core-alien-thing tried to transmogrify Mrs Munch, causing her to crash the family cart, but then changed its mind when Edvard bumped into the tree trunk releasing bark and the dust.

On my visit to Oslo, investigating those pertinent and connected events that took place at end of the nineteenth century, I, Tarquinius W. Peterson found the source. The Screaming Tree!

The Screaming tree in Oslo, source of The Scream by Edvard Munch.

More

Another semi-interesting development of The Scream—although not very interesting—was an upload by a teenage hacker to the graphics server of US Government Department of Energy, which appeared as a background-image on every webpage.

The unknown hacker stated his growing concern with an increasing existence of radioactive waste, turning up as utilitarian barbecue stands at highway rest stops and countryside picnic areas. Tarquinius W. Peterson chooses not to show the non-language-specific image, because, well, frankly it’s rubbish, but if you are interested, it’s <here>.